On the Characteristics of an Effective Consent Signal

What follows is the written copy of my comments to the California Privacy Protection Agency. I spoke to the CPPA on behalf of The Washington Post about privacy law and rights to opt out.

Hello, I am Aram Zucker-Scharff, the Lead Privacy Engineer for The Washington Post and Senior Solutions Engineer for our Zeus advertising technology group, which serves over 100 news sites. I also co-chair the W3C’s Community Group focused on Private Ad Technology and contribute to other groups to speak on issues relating to the intersection of business, privacy and advertising. I led and lead The Washington Post’s technical work around complying with California Privacy regulations. Today I’m speaking on behalf of The Washington Post.

The Washington Post was able to seamlessly roll out CCPA compliance for our California customers. When it became clear that the United States Privacy API (or USP API), as defined by the Interactive Advertising Bureau (the IAB), would become the industry standard for publishers and advertising systems we were quick to adopt it. It is encouraging that a user with a little technical experience can interact with and understand the output of the USP API in clear text.

The idea of the technical signal warrants further exploration as it could have an adverse effect on businesses. Advertising is one of the main streams of revenue at The Washington Post. In the world of digital display advertising we count load times and the time to first-ad-shown in milliseconds, and have found that every millisecond counts, and adding extra loading time can have significant cost implications. Handling multiple technical signals, not having a single standard and instead processing multiple such signals, any of which could be built on technology that itself introduces a delay, would be a significant burden for publishers. It would mean extra code on page, engineering hours to build and maintain that code, and–depending on the shape of that technology–additional delay as we waited on a response from the system.

This is why it was crucial for me to be involved with the group that created the Global Privacy Control. So many of the potential pitfalls and problems that could come out of a technology-based control were avoided in its creation. It does not require complex negotiation with an API, it does not deliver a Promise–a technical concept in Javascript which would cause us to anticipate a delay in response–and it does not require complex calculation or decoding.

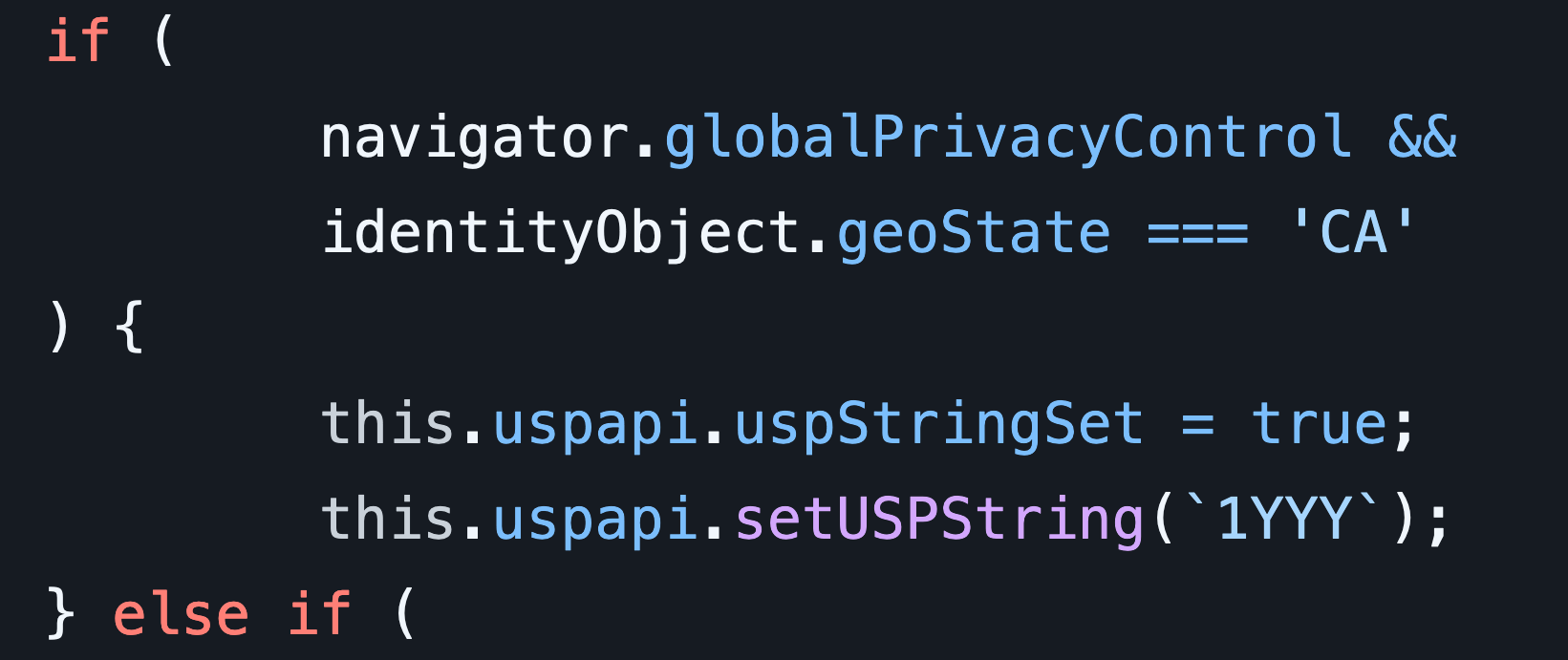

When the GPC specification was ready it was easy and straightforward for us to implement it. The entire change that was needed to support GPC on The Washington Post was 7 lines of code, less than One Hundred and Sixty Characters.

I’m prepared to show the actual code we have actively on our website to make clear the low lift for implementation:

When this code runs it sets the response in our systems to follow the user’s opt-out preference and is picked up by every relevant piece of ad and tracking technology on the page and either alters their behavior or is passed downstream the same as a manual opt out process.

The Washington Post takes these 7 lines of code and has them integrated into our CCPA compliance mechanism that processes user status with the USP API. This happens on every applicable page of our website. Once this code runs and processes the signal it is available for any other system that might need to know about a user opt out. The setting of the USP API in this way passes the signal to all downstream providers who then can comply with it. This code easily alters the state of the toggle we provide for California users, to display that they have selected Do Not Sell mode, making it visible that the user has selected it. We think of it as a robot for clicking that toggle.

With GPC, the opt out process actually occurs even faster than it would normally. Of the ways we handle compliance, GPC, in our engineering experience, has proven the fastest and most straightforward. We can also see the GPC HTTP header on any request where the user has it on and make a decision about how to handle it before the page even loads.

Our experience shows it is important to have clear, fast and transparent ways for a user to opt out and for a site to receive that opt out.

Because the user’s privacy setting and the GPC signal itself are available on every page it can be easy to note to the user it is detected, and we have a variety of options to act on that: we can restrict particular technologies, display the user’s opt out status, and make privacy-compliant ad calls as close to instantly as we can get.

Our hope in speaking here is to make clear our experience implementing California privacy law and the ease of use of the Global Privacy Control for opt-out. As rulemaking is being considered we think that what we have described is the required characteristics for a technologically appropriate signal: fast, clear, and easily integrated into existing practices. We believe these properties make GPC a signal in the best interest of our readers, ourselves as a publisher, and the ad technologies we collaborate with; one that can be used to understand an opt out under CPRA; and we wanted to make our experience of early adoption clear and urge continued support of this methodology.

We appreciate the opportunity to speak here.

I wrote this on behalf of The Washington Post, who is my employer, and it is published here with their permission and review.

Let's talk about this post:

Tweet to me Tweets about @Chronotope's #GPC